Yes, poverty does exist in Switzerland. Although the country ranks at the top of most global indexes, from Innovation, to talent competitiveness and human development, and toward the bottom of the GINI income Inequality Index, recent images of people standing in long lines in Zurich and Geneva for groceries have stirred the public. Covid19 made the lingering hardships visible - and aroused debates on the issue of the present wealth gap. Christoph Schmocker, CEO of the Julius Baer Foundation, talks to Lorenz Bertsch, Head Social and Debt Counselling Services at Caritas in St. Gallen, Switzerland, about what it means to be poor in Switzerland, how (advantaged) people can get engaged and what needs to change to prevent anyone from sliding into the poverty trap.

Mr Bertsch, how do you define poverty in a wealthy country such as Switzerland?

Being poor means earning a salary that is below or close to the poverty line. On the one hand, this concerns people living off of social welfare; on the other hand, however, this affects many people working full-time but for such a low salary that they are close to the poverty line – the so-called working poor. They pay all the monthly expenses and worry every month if they still have enough to buy groceries.

Is there a precise number defining the poverty line? Are we talking a monthly salary of 3000 Swiss Francs or a certain income per month?

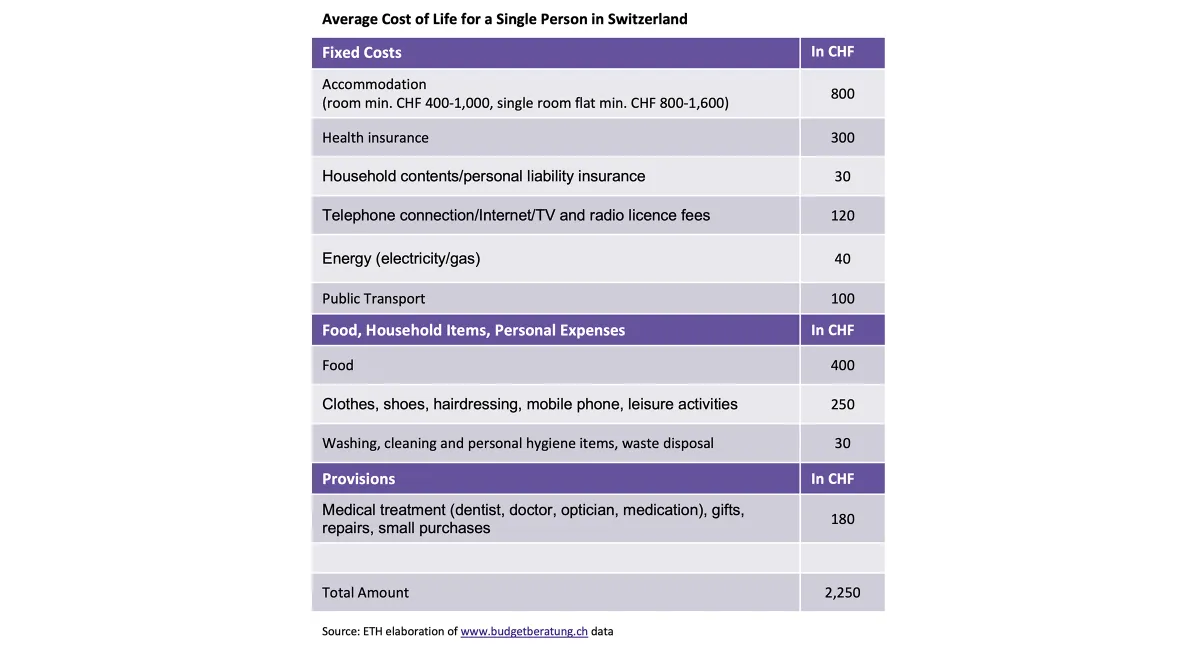

For a single person, the limit is about 2100 Swiss Francs per month, depending on where they live. That includes all costs of living, from paying the rent to medical insurance. For a single mother with two children, the threshold is at around 3500 to 3600 Swiss Francs.

From your experience as a counsellor, could you give us examples of people that struggle to make ends meet?

That could be a single mom with two children working part-time on an hourly basis and, therefore, earning a meagre salary. Every month she is confronted with whether the money will suffice to buy groceries for the kids and herself. Another example I just had a while ago: a 55year-old man who would retire in ten years but lost his job two years ago. He has sent out 500 applications and still has not found employment. He is aware that he has one month left, and then unemployment benefits will cease, and he will draw from social welfare. I asked him what it meant for him and his social environment. The lack of finances was not the worst thing for him, but being lonely. His friends have abandoned him; nobody wants to deal with him because he is unemployed and socially unacceptable.

Does this person put himself into this role because he is ashamed or does not feel taken for full because he cannot participate in the same festivities or events? Or are both sides responsible for these feelings of rejection?

I perceive it as a vicious cycle. If you are unemployed or even sick, after a while, you realise that your friends turn away and do not invite you to parties anymore. And, of course, poor people are ashamed and retreat. They do not want to go out into public anymore because they perceive that people look down on them and see them as unpresentable. In this sense, it's one's own initiative to be lonely, but poor people often get left alone and are excluded.

It’s a fact that anyone can slide into poverty. I can say from my experience that it can go very fast.

I am concerned about this categorisation of poor people. Mr Bertsch, can it happen to me, too? What are the triggers that in six months I could find myself being poor?

It's a fact that anyone can slide into poverty. I can say from my experience that it can go very fast. You can get sick or unemployed or get a divorce, and your income drops significantly, and then things go very quickly. Every single person has to be aware of this.

I can see certain patterns, financial and emotional ones. Are there other reasons why people slide into poverty?

From our experience in our counselling offices, we can say that the most significant risks for being poor here in Switzerland are unemployment and illness. In both cases, the income drops to 80%. From one day to another, a family with two children earning 4000CHF a month has to cope with 3200CHF. There is not much left to buy groceries after paying for rent, medical insurance, and other fixed expenses.

A socio-political problem, in our opinion, is the minimum wage or the lack of it. Often in our counselling sessions, we would see monthly wage statements of 3000CHF for a full-time job. Recently, I had the lowest salary in the retail business: full-time work for 2000CHF. Not all industries have a minimum wage, and that's the problem. There are sectors, such as retail, cleaning services or industrial assembly-line work, where salaries are extremely low.

According to Caritas Switzerland, the outbreak of Covid19 triggered the most extensive relief campaign since World War II. Swiss civilians, companies and institutions donated over 13 Million Francs to Caritas to support people that were financially hit hard by the pandemic. Bank Julius Baer reacted immediately donating 2.5 million CHF to Caritas to face this emergency.

Even though government subsidies enabled corporations to avoid layoffs by temporarily securing 80% of the salaries, the missing 20% were vital for many people.

The critical point is that the governmental tools target the broader middle class, leaving the lowest strata in the Swiss society struggling. Caritas tried filling the gap by using the generated donations as quick emergency aid for people in need. Among other things they temporarily paid for medical insurance fees, rents or food to prevent the families from sliding into the poverty trap.

Some cantons have initiated developing such tools for quick relief on a governmental level. Caritas Switzerland welcomes such initiatives. People slide into poverty extremely quickly, but it takes years for them to recover and find their way out. Therefore, quick relief aids make absolute economic sense to the non-profit organisation. It demands more such initiatives to catch the people before they fall.

About one third of all people living in poverty in Switzerland are children. Growing up with a lack of resources, they are very likely to live in poverty all their life. They are free of blame. Their opportunities are limited – only through birth.

In Switzerland, there is a widespread perception that being poor is one’s own fault and responsibility. Out of experience, we [Caritas Switzerland] can say this is simply not true.

Mr Bertsch, when someone is in the situation of being poor, could you tell us about the consequences over a long period?

The effects of poverty are extensive. The people coming to us confirm this. In society, people associate poverty always with not having enough money. However, we notice that the social aspects are way more burdening. Our clients come to us saying that having no money is bad, but their loneliness is much worse. They cannot talk to anyone; they don’t get touched. They are secluded; it is social isolation. And what I can often observe is that poverty makes you tired. They sit at our table and say, ‘I can’t anymore’. Poverty strains relationships. There can be fights; there can be addictions resulting from it. And poverty can make you sick. Living in poverty means being at higher risk of falling ill.

They are secluded; it is social isolation.

However, there is hope. In the past years, Caritas can detect a trend towards more social entrepreneurship. It can be economically attractive for organisations to socially invest parts of their profit in the field they operate in. Such investments potentially stimulate reciprocal actions, ultimately benefitting all.

During Covid19, Caritas' offices have received as many inquiries and as much willingness to get engaged as never before. Corporations are becoming aware of their obligation. Wherever there is a significant wealth gap, the economy is weak. When buyers lack the means, there is no consumer purchasing power. It is vital for all, disadvantaged and advantaged, entrepreneurs and consumers alike, to have a more equal distribution of wealth.

Opportunities to get engaged are numerous for civilians, such as in neighbourhood aid or other forms of community service. Relief organisations are open to innovative forms of collaboration between corporations and the non-profit sector to address wealth inequality in a broader and more systemic approach.

Lorenz Bertsch is Head of Social and Debt Counseling at Caritas St.Gallen-Appenzell. With a background in industry and business administration, Lorenz switched to the social sector at the age of 32, focusing mostly on mental disorders and disability, while also working in marketing and quality management. Ten years ago, Lorenz Bertsch joined Caritas. He works mostly with people affected by poverty, as he advises and supports them through solutions that reduce their financial exposure. In addition, he is responsible for social policy, with the aim of improving the framework conditions for people affected by poverty.

Christoph Schmocker has been the CEO of the Julius Baer Foundation between 2016 and 2022. Before joining the company, he lived for six years in South Africa, where he was Director of Fundraising and Strategic Projects for the University of Cape Town (UCT). Prior to this, he worked for ten years as CEO of the UBS Optimus Foundation where he developed the focus of the UBS philanthropy strategy. As a philanthropic advisor, he continues to develop strategies for multiple grant foundations. From 2007 until 2019, he served as Vice President of the Board of Trustees of the Roger Federer Foundation. He has been a member of the Zeitz Foundation since 2019.