We feature an interview made in collaboration with one of our Partners, The Nature Conservancy.

Robyn James, Director of Gender and Equity, Asia Pacific Region of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) leads us to an interesting analysis on the importance of cooperative and sustainable management of grasslands, the intersectionality between wealth inequality, gender inequality and climate change and in particular how we can build a sustainable future.

- Could you elaborate on how efforts to narrow the gap between rich and poor in parts of Inner Mongolia intersect with gender inequality?

Data shows us that the link between gender and wealth inequality is universal. Globally, women do nearly three times as much unpaid work as men. Women are primarily responsible for caring for their families and communities and especially children. And many herding communities are no exception. This high workload for women means that they are time-poor and struggle to participate in community meetings and trainings relating to better grassland management. This means that all efforts to narrow the gap between the rich and the poor must consider gender. We simply cannot address this problem without understanding how economic systems and markets impact women and men differently. When we understand that, we can be intentional about designing programmes with and for women so that they too are benefiting from efforts to narrow the gap between the rich and the poor across groups such as herders.

- How does climate change exacerbate the existing wealth gap among herding communities, and what role does sustainable land management play in addressing this issue?

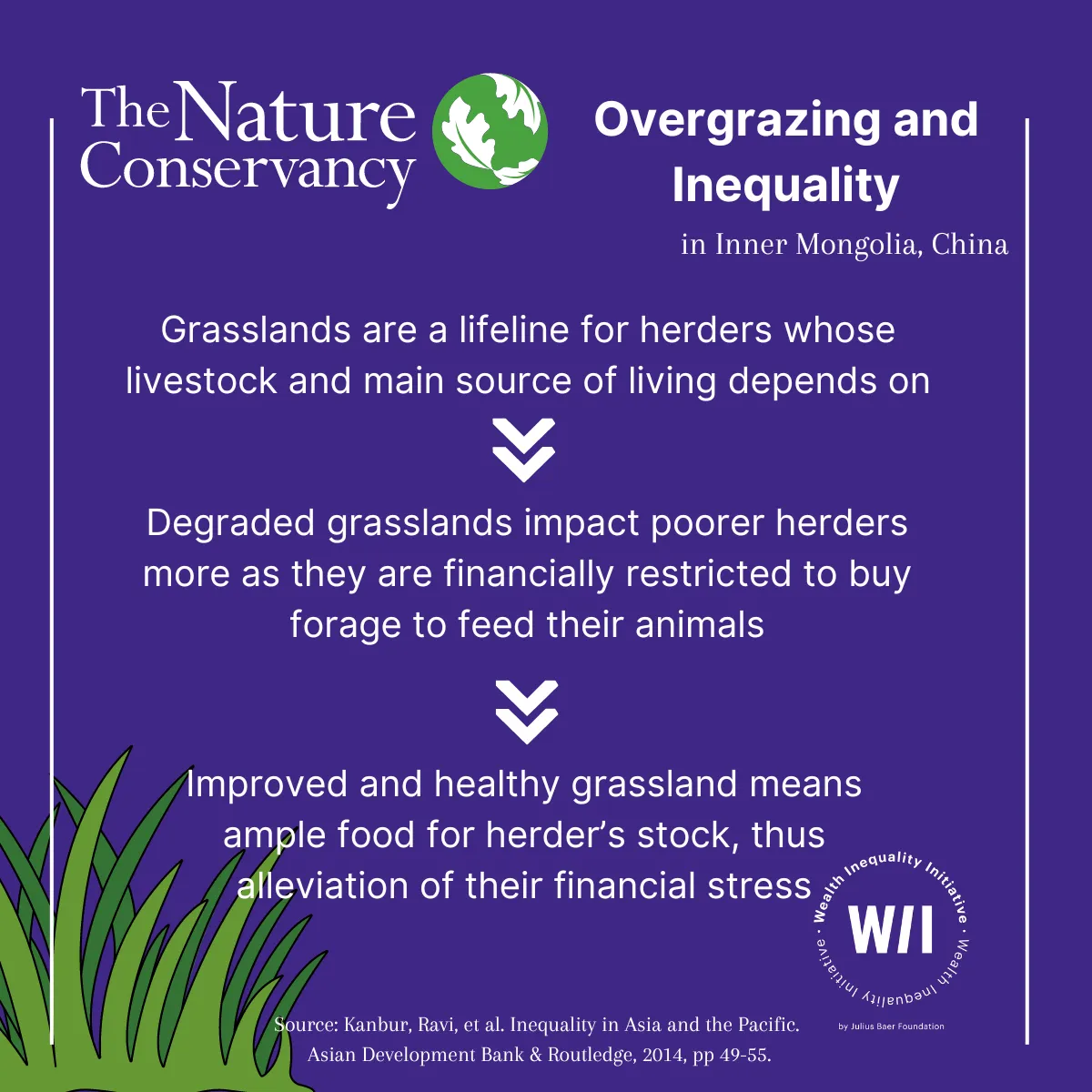

Grasslands are at the heart of culture and commerce in Inner Mongolia. Yet desertification driven by climate change, combined with overgrazing, has degraded an estimated 90 percent of all land in this region. Seasons and rainfall are now increasingly unpredictable, which has severe consequences for the grasslands. Because of these conditions, small farmers are not able to produce enough food for their cattle and are forced to buy forage to keep their cattle fed during winter. With this added cost, annual expenses often exceed their annual income.

Without a shared approach among all herders to embrace sustainable management, this cycle of economic stress may spin out of control. And Inner Mongolia’s grasslands likely will experience ever-greater pressure from climate-driven changes in weather and temperature that strip topsoil and can turn once-plentiful grazing areas into barren landscapes, as we have sadly seen in other parts of the world.

- Could you give us more detail on how TNC's Grassland Smart Management (GSM) and the Spring Support Plan are designed to address narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor among herding families in Inner Mongolia?

TNC is training herders in Grassland Smart Management, a way to sustainably graze their lands in ways that will return them to resilience and health. Our focus is on a shared land management approach that brings together wealthier and poorer herders around a common goal. By bringing together these different perspectives, the programme facilitates a collective understanding of modern challenges faced by the community and encourages collaborative efforts to develop solutions that benefit all its members.

To narrow the gap TNC supports poorer herders, who cannot fully afford forage feed, to access this critical resource and allow for grazing lands to rest in early spring for greater yield later in the year. If these herders practice GSM on their lands, they only pay back 50 percent of the loaned forage. This incentivizes sustainable practices and helps herders to eliminate their debt as well as reducing their need to overgraze their land or to rent it out to wealthy herders.

- Why is the partnership between The Nature Conservancy, Julius Baer Foundation and local stakeholders needed to address narrowing both the gap between the rich and the poor, and the gender gap?

The partnership between TNC, Julius Baer Foundation, and local stakeholders is a great example of diverse partnership to address systemic socio-economic gaps. We can leverage collective expertise, resources and community engagement. By working collaboratively, we can develop and implement holistic solutions that not only address immediate challenges but also promote long-term sustainability and resilience among herding communities in Inner Mongolia.

- How do you envision the long-term impact of TNC's initiatives in Inner Mongolia on both the wealth and gender gaps, and what are your hopes for the future of these communities?

My hope for the future is that global markets increasingly value our natural systems such as grasslands as being as important as money. I think of healthy, thriving and productive grasslands as like a healthy bank account and investment portfolio. It can withstand shocks like climate extremes much like a healthy investment portfolio can withstand stock market shocks. And by considering the fairness in the use and distribution of natural resources, that investment can benefit all, not just a few. That is my hope for the future, that our planet and the people who depend on it and are most marginalised are as important in our economic systems as the top few.

Wealth inequality and the climate and conservation crises are inextricably linked. Rich countries are driving the climate crisis, while those living in poverty- especially marginalised groups - are paying the price

Director of Gender and Equity, Asia Pacific Region of The Nature Conservancy (TNC)

About The Nature Conservancy

Make an impact that lasts a lifetime — discover opportunities at The Nature Conservancy to donate, volunteer, work, and learn.